How Mental Fatigue Impacts Physical Endurance: Boost Your Performance

As the Tour de France enters its final week, an insidious and underappreciated element is adversely impacting riders’ performances. Regardless of your athletic level, understanding this just might change the way that you approach training and competition.

We have known that brain (central) fatigue impairs muscular endurance since the late 1800s. More recently, we have discovered the reason. Both physical and mental loads burden common brain networks that, among other things, contribute to our sense of perceived exertion. This matters because your perception of effort, rather than your muscles, is what “grabs the brakes” on performances lasting over a minute.

Put differently, even if your legs are fresh, a fatigued brain will make the same workload feel much less tolerable. Rachet the intensity up a few notches and even the most hardened athlete will pop sooner than if their brain was less burdened. Ordinarily this is a good thing, the brain’s highly conservative way of reeling us in long before we are risk of over-exertion. When seeking to push closer to our physical limits in competition, however, it’s an obstacle.

As a career brain scientist turned performance coach, I am stunned by how frequently overlooked this reality is even at the topmost levels in endurance sports. In this regard, we lag far behind sports like soccer, tennis, and Formula One. There are two ways forward.

The first is to ensure adequate recovery for the brain as well as the legs. Sleep is widely appreciated as critical, but so is reducing as much of the mental load experienced outside of competition as possible. This includes limiting social media engagement and video games that unnecessarily stress the brain. For many athletes there is ample room for improvement here. Unload the brain.

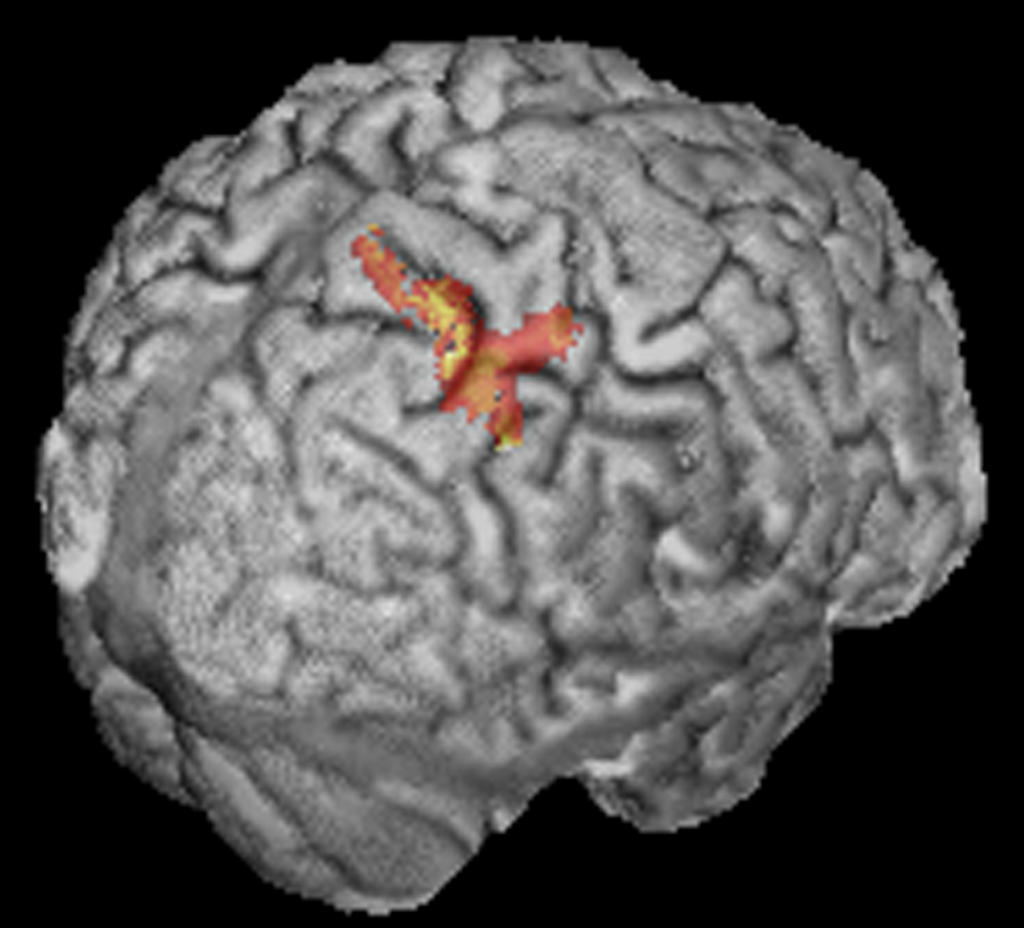

The second is more involved and takes advantage of our brain’s extraordinarily capacity to reconfigure itself adaptively to challenges (i.e., neuroplasticity). Like a muscle, the brain gets stronger through repeated overload and rest. My field has developed tasks to selectively challenge and train particular brain networks (see accompanying image). Progressively adding a targeted neurological workload to an athlete’s normal training program can lessen the impact of accumulating stress and brain fatigue on perceived exertion, focused attention, and critical decision-making. The research indicates that athletes trained in this manner are more resilient and robust to fatigue when it matters most.

Like all training, getting this recipe correct is both a science and an art. Beyond expertise, it requires experience, communication, and commitment. The key principles at work here are familiar to coaches and athletes alike— specificity, individualization, and progressive overload.

I am convinced that the marriage of neuroscience and sport science offers the potential for better than marginal gains and am excited to be helping athletes looking for a competitive advantage realize this potential.

Image: Focused brain activity captured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Colored regions reflect average brain activity as participants in my lab performed a task that demanded highly focused visual attention. This illustrates how specific behavioral tasks can be used to stimulate particular brain networks, resulting in improved function. From Gerry & Frey, 2006. Journal of Neuroscience.