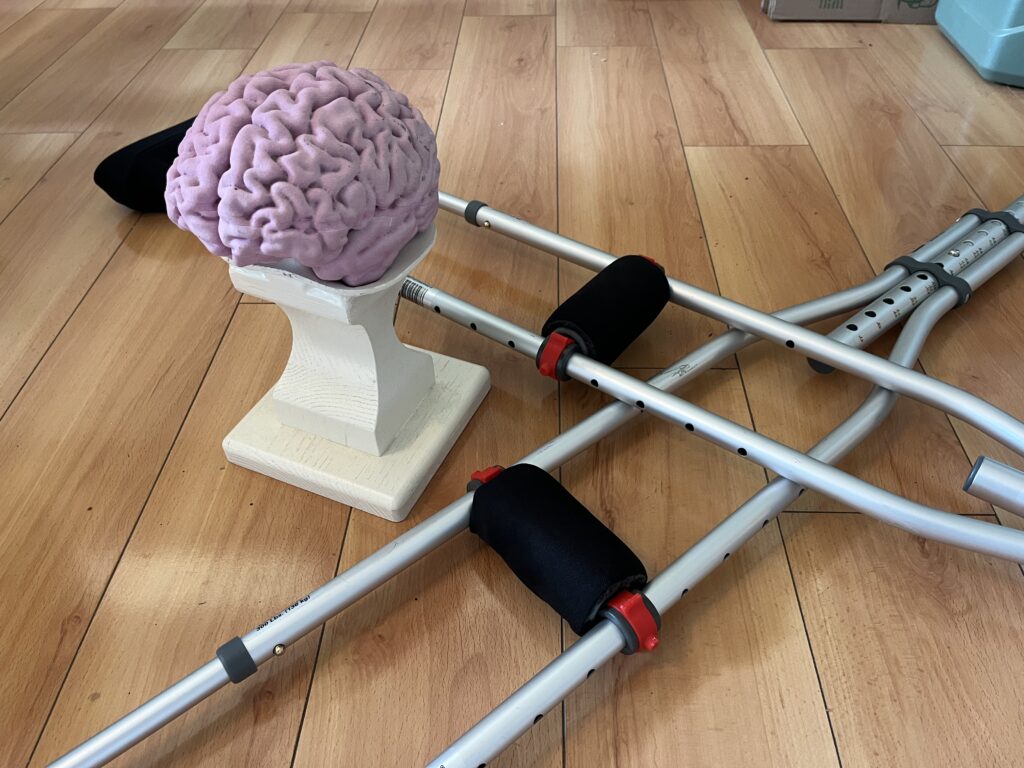

A Brainy Approach to Navigating Injuries

There are two types of cyclists, those who have fallen and those who will. Having recently cracked my femur while in a mountain bike spill, I can attest to the accuracy of this statementWhether you ride bikes, run, ski, etc., there will likely come a day when you will be sidelined by injury. The game then shifts to figuring out ways to preserve as much of your hard-earned fitness as possible while recovering.

As an athlete and cognitive neuroscientist, these are the things that I am doing to ensure that I minimize the impact of this detour on my fitness.

Leverage the Cross Education Effect. Not using a limb due to injury results in rapid decreases in strength and muscle mass. However, our brains are wired such that continuing to strength train with the healthy limb. Research indicates that this can slow the loss of strength in an immobilized limb by up to 30%. For me, that means adapting my strength training sessions to continue working my good leg, upper body, and core.

Maintain Your Tolerance for Discomfort. Remember how hard the first intervals of the year feel after not pushing your level of perceived exertion for a while? Our ability to sit in the pain cave unflinchingly during hard workouts and races is essential to high performance. It is also a trainable skill. Building tolerance for effort-related discomfort involves driving neuroplastic adaptations in a particular brain regions—our “willpower” network. When sidelined by injury, we can keep this system tuned up by regular doses of voluntary discomfort. In my case, that takes two forms—passive and active. The active part involves pushing intervals in the swimming pool with a buoy to eliminate the kick and working the skierg. The passive doses come about through voluntary cold exposure (cold plunge). In addition to positively influencing metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and regulation of the autonomic nervous system, this is a potent stimulus for the “will power” network that helps maintain our ability to tolerate discomfort.

Watch Great Athletes. When we observe others performing skillfully, brain networks involved in planning and coordinating our own performances are stimulated. We can amplify these effects by imaging ourselves moving along with the athlete being observed. You can see an example of this brain activity captured my homepage.

Together, action observation combined with motor imagery is a powerful stimulus for performance-critical brain circuits that will help you maintain, and possibly even improve, your technique during a hiatus.